Robert Andy Coombs’ work is singular. The artist creates images so beautiful and compelling that they’ve become part of the canon of queer visual culture. Jerry Saltz, senior art critic for New York magazine, called Coombs’ photography “among the most unshakeable new work, by a new voice, I have come across in years,” and it’s easy to understand why. By exploring the intersection of sexuality and disability Coombs has created a striking catalog of images. (Note for those who google him: some of Coombs’ work is not safe for work.)

This past summer, New York City Tourism commissioned the artist to make a photographic diary of his experience during NYC Pride. Coombs is familiar with the City, having frequented the five boroughs while earning his MFA at Yale; earlier he completed his undergraduate degree at Kendall College of Art and Design in Michigan, where he suffered a spinal cord injury and has used a wheelchair since. Photographing NYC Pride is no small task: the event is a sprawling affair of happenings across different boroughs, attended by hundreds of thousands of supporters. Coombs took his camera to Harlem Pride, the Queer Liberation March, historic gay bars Julius’ and the Stonewall Inn, and other locations across the City. We talked to him about his weekend, accessibility in queer spaces and why he loves NYC.

Saturday, June 24: Julius' and Stonewall Inn

There’s so much going on at New York City Pride, so I’d love to start with your itinerary for the weekend. What did you do?

Robert Andy Coombs: I just played it by ear. I wanted to do less of the corporate stuff and more just show the experience of being on the street and maneuvering around the City as a wheelchair user. I really didn’t go out at night, either—I was so tired from photographing all day and overwhelmed by how it can be for someone with a disability.

Saturday, June 24: Harlem Pride

Tell me a little bit about your process and your relationship to photography and the camera.

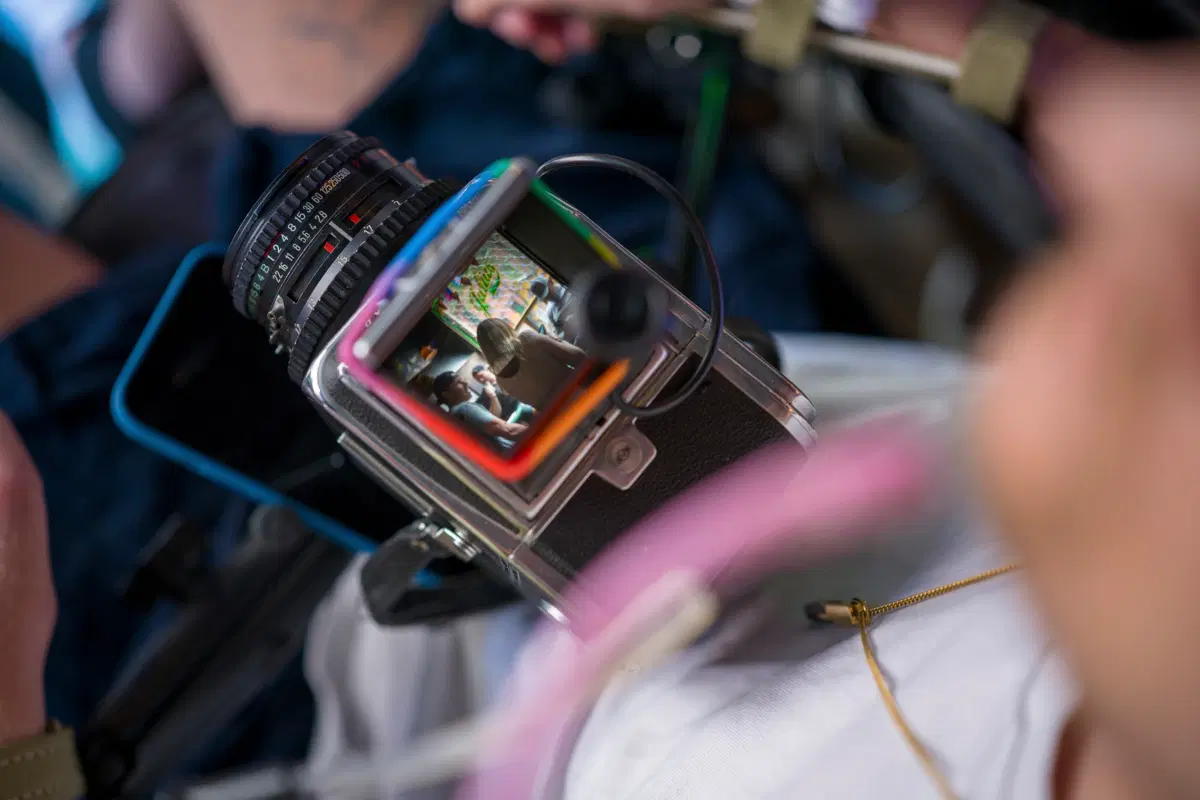

RAC: My process has evolved over time. However, even before my accident, I always worked with a group of friends on my photo shoots. I am in front of the camera, but I take control of everything; lighting, settings on the camera, directing my photo assistant on where to go and what to photograph, reviewing the photos and more. I usually know what I want before a photo shoot, but I always leave room for experimentation and suggestions from my creative collaborators.

I have always been interested in the art of self-portraiture and loved photographing myself and my body. I’ve had a pretty good relationship with my body image. I love the way I look and I love what my body does for me, even though it doesn’t look or work the way it used to. I also need to photograph my body to take care of it. If my caregiver notices a pressure sore, I need to take pictures of it to see what it looks like. That way I can address it while also documenting its progress of healing. So photography is extremely important to every aspect of my life.

Photography is also a huge outlet for me, because I am so limited in what I can do physically. Photographing is something physical I can do to get everything that is going on in my brain out into the world. I started experimenting more with street photography when I was studying at Yale. I would venture into NYC from New Haven and explore the City. As a wheelchair user I am at a lower vantage than most people, and I love showing the joy of traversing the streets, crowds and queer spaces from that perspective.

Sunday, June 25: Queer Liberation March

I imagine all of that is heightened at Pride, since it’s such an unpredictable environment. How was the actual March itself?

RAC: As with most queer spaces, it was tough. I tried to focus on shooting mostly other disabled people and other wheelchair users to show what it’s like from our perspective and how overwhelming it can be to be in a sea of people standing and walking around you and not paying attention. I did get to see a lot of friends, though, which was fun. And I got to talk to a lot of great people.

Yes! I noticed a few pictures of Ryan McGinley. He’s a friend, mentor and hero of mine. I actually found out about your work through him. [Ed. note: McGinley is a renowned fine-art photographer.] What’s your relationship like?

RAC: I’ve been a fan of his work for quite a while. I got to meet him when he came to give an artist talk at Yale. Then we had a studio visit together where we spoke and became friends. Ever since then he’s been a huge champion of my work and really understood my vision. I was moved because he kept saying that he was blown away by my work. He was like, “I rarely see something new, and this is definitely something I’ve never seen before.” That meant a lot to me. And then being able to see each other out and about [at Pride; see the following two photos]…was a really fun experience.

We spoke earlier about Pride and accessibility. What are some things the queer community can do to become more accessible, during Pride and in general?

RAC: Woof! That is a big question. To start, we need to make sure that buildings, bars and landmarks are accessible. People like me, who are in 300-pound wheelchairs, are not easily lifted up. So we need to make sure there are elevators or lifts that are actually working, receive regular maintenance and are not being used as storage areas.

[But] most of all it’s the lack of interaction that we get with our peers. When I go as just myself and not a photographer, I tend to become even more invisible. People don’t pay attention to me. Rarely do people come up and talk to me. I love dancing. I love hitting up people and flirting and all that stuff, but if I go up to someone and want to dance with them or talk to them, they just think that they’re in my way. They’re like, “Oh, sorry, we’ll move,” and I’m like, “Well, I wanted to interact with you.” Things get lost in translation when someone’s standing and I’m sitting and trying to talk to them in a loud, crowded place.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t have loud music in bars and clubs. [I’m talking about] this lack of empathy. I think a lot of us had traumatic upbringings being ostracized and bullied, so we built really tough exteriors, and that’s understandable. I often feel that because I am a wheelchair user and have a disability, people automatically don’t think of me as attractive, so that’s really difficult.

I feel like when gay men look at me, they see their own mortality and fragility. I think this all has to do with trauma from the AIDS epidemic, when we lost a whole generation of amazing queer people. Others were always taking care of these people who acquired the disability of having HIV and AIDS. And it’s just like, where did that empathy and love go?

Do you find that empathy and love in NYC?

RAC: I love New York and I love visiting. And the queer community in New York is a little bit more accepting. I’ve always had a good rapport with the other queer artists in New York—that’s where I found most of my collaborators and friends. I love living my fantasy in New York and being able to collaborate with all these other amazing queer artists who are so accepting and really are big champions of my work. They get my vision. New York will always have an amazing spot in my heart.

A whole team contributed to the weekend's shoot and the making of this piece. Pictured below are Robert's photo assistants, producer, production assistants and caretaker, in front of the West Village Piers. (From left) Kullan, Nava, Vanessa, Marshall, Bell and Gus

And Robert with the writer, Adam Eli, during the Queer Liberation March.

Find more LGBTQ+ and Pride-related stories here.